“My soul is full of longing

for the secret of the sea,

and the heart of the great ocean

sends a thrilling pulse through me.”

― Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

“If money go before,

all ways do lie open.”

—Shakespeare, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 2

Scene 2

|

| “If money go before, all ways do lie open.” |

It’s fun perusing old Dragon issues. You never know what

you might find. Those dusty old volumes are chock full of wisdom, where sages

of campaigns past dealt with subject matter Mr. Gygax might not have thought

about, or deemed too esoteric to be included in the original DMG. There was

only so much that could be crammed into it, after all.

This is not to say that there is not a lot in the DMG; because

there is. Sometimes I wonder whether there was too much in it to be fully absorbed.

It’s a wonder of inclusivity; all you might think a DM might need, including

such minute as dungeon dressings and herbal lists, randomized sights and

sounds, air currents and odors, even container contents…ad nausea.

That said, there is nothing within it about trade and

commerce. Or any edition, for that matter. There is a great deal of talk about

trade, but nothing about its application. What it does cover is combat, magic,

and magic items. And more; so much more.

There are descriptions of watercraft, and their potential

speed; there are tables to generate wind speed and direction, and when crew

exhaustion might set in. There are rules to adjudicate the possibility of

damage to watercraft inflicted by wind, from fires; rules on ramming; and how

quickly a vessel will capsize and sink.

These are all important, especially if the PCs are

aboard.

Less so, if they are not.

If they are not, the PCs will likely only want to know

their return on investment.

I thought, “What about the Wilderness Survival Guide?”

I should have realized that the title might hint at its

contents.

The Wilderness Survival Guide goes into even more detail

about movement and weather. Excruciating detail: There are even tables

concerning vehicular encumbrance.

It even has a passage concerning the use of a capsized

vessel:

Because of the

natural buoyancy of the materials from which they are made, most vessels can

remain “afloat” just beneath the surface of the water even after they are

capsized or after they have suffered hull damage. However, this is true only of

vessels that are carrying no passengers and not more than 10% of their listed

maximum cargo capacity. For example, if characters in a small rowboat that is

foundering can get out of it and toss overboard all but 200 gp worth of their

cargo or gear, the craft will sink to slightly beneath the surface of the water

and remain there. It is then possible for characters to cling to the sides of

the craft and use it as a flotation device, as long as their weight is evenly

distributed. A capsized craft will support a number of characters equal to

twice its normal capacity; that is, up to eight characters can cluster around

the sides of a large rowboat and use it to keep from going under themselves. If

this weight limit is exceeded, or if the weight is not evenly distributed, the

craft will sink too far below the surface to be usable in this fashion. [Wilderness Survival Guide – 46]

It defines each type of terrain and body:

Seacoast

Simply put,

practically any place that is a short distance from an ocean is seacoast

terrain.

Swamp

In game terms, a

swamp is any place where a character’s feet hit standing water shortly before

hitting the ground. Swamps are always located at low elevation or on flat or

slightly depressed land at the edge of a river or lake. […]

The depth of the

standing water in a swamp can vary from practically zero (where the ground is

merely spongy) to several feet, and sometimes goes from shallow to deep in the

space of just a few steps if the underlying terrain is irregular. Movement

through a swamp can be very difficult, if not actually dangerous, and a swamp

is not a good place to take mounts or pack animals. If the shortest distance

between two points would take characters on a path through a swamp, they would

be well advised to circumvent the soggy area and spend a few more steps to get

where they’re going. But if their destination is inside the swamp…well, even if

the adventure isn’t wild, it will certainly be wet.

Bodies of Water

In a typical

campaign world, rivers and lakes serve at least two important purposes: They

provide a ready source of water, and their presence requires a party of

adventurers to be more versatile. A body of water is both an opportunity and a

challenge. Travel on the surface of a lake or river is often faster, easier,

and safer than negotiating the surrounding terrain on foot—but only if

characters have access to a boat or a barge and someone in the group has the

skill to handle the craft expertly. Swimming across a deep, wide river, instead

of following the shoreline and looking for a place to ford, can save hours or

even days of travel time—but only if characters have the ability to swim in the

first place. [WSG – 9]

I’d have thought that each was self-explanatory, but there

are those DMs who like things spelled out.

The DMG was more useful in this regard:

Lake assumes a large body of water, at least two to three miles broad and several

times as long, minimum.

Marsh assumes a shallow body of water overgrown with aquatic vegetation but

with considerable open channels; this does not include a bog but does include

swamps.

River assumes a body of water at least three times as wide as the vessel

afloat upon it is long (that is, the smallest river is at least 40' wide) and

navigable to the vessel considered, usually because of familiarity and/or

piloting. For current effect, subtract its speed times eight (C X 8) from

movement when moving upriver, adding this same factor to movement for downriver

traffic unless navigational hazards disallow—in which case adjust to a

multiplier of two or four times current accordingly.

Sea (and ocean) movement assumes generally favorable conditions. It is not

possible to herein chart ocean currents, prevailing winds, calms, or storms,

for these factors are peculiar to each milieu. Currents will move vessels along

their route at their speed. Prevailing winds will add or subtract from movement

somewhat (10% to 30%) depending on direction of travel as compared to winds.

Calms will slow sailed movement to virtually nil. Storms will have a likelihood

"f destroying vessels according to the strength of the storm and the type

and size of the vessel. To simulate these effects during long voyages, reduce

the movement rates shown by a variable of 5% to 20% (d4, 1 = 5%, 2 = 10%.

etc.).

Stream assumes a body of water under 40' width. The effects of currents are

the same as for river movement.

[DMG 1e - 58]

Did I mention that I would include all water borne

transport in this piece? Trade is trade, regardless whether it’s shipped

upriver or down the coast.

For the most part the Wilderness Survival Guide concerns

itself with…wilderness, and not the Deep Blue Sea. The DMG is more helpful. Not

only does it defines the roles of the crew onboard, it also suggests what each

earns.

Ship Crew:

As with a captain,

crewmen must be of the sort needed for the vessel and the waters it is to

sojourn in. That is, the crew must be sailors, oarsmen, or mates of either

fresh water vessels or salt water vessels. Furthermore, they must be either

galley-trained or sailing-vessel trained. Sailors cost the same as heavy

infantry soldiers (2 g.p. per month) and fight as light infantry. They never

wear armor but will use almost ony sort of weapon furnished. Oarsmen are

considered to be non-slave types and primarily sailor-soldiers; they cost 5

g.p. per month, wear any sort of armor furnished, and use shields and all sorts

of weapons. Marines are simply soldiers aboard ship; they cost 3 g.p. per month

and otherwise have armor and weapons of heavy foot as furnished. Mates are

sailor [sergeants] who have special duties aboard the vessel. They conform to

specifications of serjeants and cost 30 g.p. per month. [DMG 1e – 33]

Ship Master:

This profession

covers a broad category of individuals able to operate a vessel. The likelihood

of encountering any given type depends on the surroundings and must be determined

by the referee. Types are:

River Vessel Master

Lake Vessel Master

Sea-Coastal Vessel

Captain

Galley Captain

Ocean-going Vessel Captain

The latter sort

should be very rare in a medieval-based technology milieu. Note that each

master or captain will have at least one lieutenant and several mates. These

sailors correspond to mercenary soldier lieutenants and [sergeants] in all

respects. For every 20 crewmen (sailors or oarsmen) there must be 1 lieutenant

and 2 mates. Sailing any vessel will be progressively more hazardous without

master or captain, lieutenants, and mates. […] The proper type of master or

captain must be obtained to operate whatever sort of vessel is applicable in

the waters indicated. Cost for masters, captains and lieutenants is 100 g.p.

per month per level of experience. They also are entitled to a share of any

prize or treasure taken at sea or on land in their presence. The master captain

gets 25%, each lieutenant gets 5%, each mate 1%, and the crewmen share between

them 5%. The remainder goes to the player character, of course. [DMG 1e – 33,34]

It defines what each vessel is.

And of what travel distance it is capable, very useful

when figuring out how long a voyage might take:

Rowboat:

Small boats, with

or without a sail, which are rowed by oars or paddled, fall into this category.

A ship's longboats, dugout canoes, skiffs and punts ore likewise considered

rowboats. A normal crew for a rowboat can be from one to ten or more men

depending on its size. Rowboats do not come equipped with armament and don't

function well in breezes above 19 miles per hour.

Barges/Rafts:

These are long,

somewhat rectangular craft designed primarily for river transportation. A few

larger and sturdier types are used for lake and coastal duties. Barges

generally have a shallow draft, as do rafts—the former having a bow and side

freeboard, with the latter having neither. The Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut's

obelisk barge is a prime example of a working barge. Crafts constructed of

fagots bound together, or made of stretched hides, such as the umiak, are

considered barges in most cases. The same is true of sampans and jangadas.

Normal crew for a barge varies between 20 and 100 or more men, depending on the

size of the ship and its purpose. If the barge is a working vessel, such as

Queen Hatshepsut's, it is conceivable that it could require as many as 100 men,

if not more, to man such a mammoth barge. Sampans and jangadas, on the other

hand, do not require a great crew to man them. Sampans need only three to ten

men while jangadas require as few as one. Barges and rafts don't usually come

with armament, but can be so equipped if desired. These types of vessels do not

function well in winds above moderate breezes.

Galleys:

These are long,

slim oared ships. Some of the earlier types of galleys are the Greek and Roman

biremes, triremes and quadriremes. These galleys have 2, 3, and 4 banks of

oars. The type most commonly used in AD&D is the drakkar, the Viking Dragon

Ship. This is a square-sailed, oared ship having a single mast that can be

unstepped. She is the easiest to maneuver in choppy waters because the planks

are overlapped and riveted together (clinker built). This gives her the ability

to move with the waves instead of forcing her hull through them. Crew for

galleys depend on their size. Some can have as few as 30 men manning the oars

while others have been known to have 200 or more. Most galleys, because of the

need of space for the men at the oars, do not venture for from land. The

general construction is such that even though she is seaworthy it is more

comfortable to be near land or sail the rivers and make camp on the shore.

Armament on galleys ranges from a ram to ballistae. Some of the larger ones may

even sport o catapult. Merchant Ships:

This type of ship

is most commonly a small wide-hulled vessel having a single mast and a lateen

sail. She is not only favored by merchants, but pirates as well. She can be

moved by sweeps at rowboat speed. Cogs, carracks and caravels of the 13th and

14th centuries are considered to be excellent merchant ships because of their

sturdiness and the few sailors required to man them. Most ships of this type

con feasibly carry a hundred or more men, but because of on-board conditions and

money, ships are manned by a minimal crew of at least 10 men, including the

officers. Pirates are the exception when manning ships. They will fill the ship

with men, sailing up and down the coast for about a week, plunder if they can,

and then put into port. Typical armament for this kind of ship includes

ballistae and perhaps a catapult. DMG 1e – 53

Naval transports and their commercial counterparts

were slow, unwieldy, and nearly defenseless. As such, they were always

escorted. Navies used them to carry troops, horses, supplies, weapons, and

ammunition. Commercial transports carried bulky and heavy cargoes: grain,

cattle, stone, ore, metal ingots, etc. Cutters, sloops, and schooners were used mostly for

fishing, trade, and carrying passengers. The fastest commercial ship was the

clipper, which carried passengers and cargo that required great speed. Passage

on a clipper often ran high (500 gp would be reasonable in AD&D game

terms), and cargo rated up to 25% of the assessed value for bulky loads. The

second fastest were the packets, which usually carried passengers or mail. In

times of war, many navies commissioned packets to carry military mail and

dispatches. The small, medium, and large cargo ships were generic merchant

ships of the 16th to mid-19th centuries.

[Dragon #166 – 15]

MOVEMENT AFLOAT, OARED OR SCULLED IN

MILES/DAY

|

Vessel Type

|

Lake

|

Marsh

|

River

|

Sea

|

Stream

|

|

Raft

|

15

|

5

|

15

|

x

|

10

|

|

Boat, small

|

30

|

15

|

35

|

x

|

25

|

|

Barge

|

20

|

5

|

20

|

x

|

x

|

|

Galley, small

|

40

|

5

|

40

|

30

|

x

|

|

Galley, large

|

30

|

x

|

30

|

30

|

x

|

|

Merchant, small

|

10

|

x

|

15

|

20

|

x

|

|

Merchant, large

|

10

|

x

|

10

|

15

|

x

|

|

Warship

|

10

|

x

|

10

|

20

|

x

|

MOVEMENT AFLOAT, SAILED IN MILES/DAY

|

Vessel Type

|

Lake

|

Marsh

|

River

|

Sea

|

Stream

|

|

Raft

|

30

|

10

|

30

|

X

|

15

|

|

Boat, small

|

80

|

20

|

60

|

X

|

40

|

|

Barge

|

50

|

10

|

40

|

X

|

X

|

|

Galley, small

|

70-80

|

X

|

60

|

50

|

X

|

|

Galley, large

|

50-60

|

X

|

50

|

50

|

X

|

|

Merchant, small

|

50-60

|

X

|

50

|

50

|

X

|

|

Merchant, large

|

25-35

|

X

|

35

|

35

|

X

|

|

Warship

|

40-50

|

X

|

40

|

50

|

X

|

DMG 1e – 58

There’s even a glossary of terms to be had:

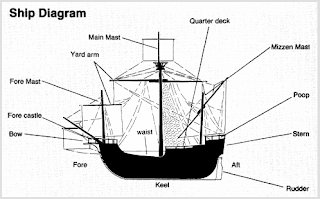

General Naval Terminology:

Aft- the rear part

of a ship. Corvice - a bridge

with a long spike in its end used by the Romans for grappling and boarding.

Devil - the longest

seam on the bottom of a wooden ship.

Devil to pay -

chalking the seam of the same name. When this job is assigned, it is given to

the ship's goof-off and thus comes the expression "You will have the devil

to pay".

Fore - the forward

part of a ship.

Fore Castle - a

fortified wooden enclosure resembling a castle in the fore Hoist Sails- to

raise the sails. Lower the sails- to let the sails down.

Port - the left

side of a ship; also a city or town where ships may take refuge or load and

unload cargo.

Shearing off oars -

accidentally or intentionally breaking oars of one or more ships when

attempting to board or cripple the ship if it did not retract its oars of a

ship.

Starboard - the

right side of a ship.

Step- to put the

mast up.

Stern - a section

of the aft of a ship.

Stern Castle - the

same as a fore castle except that it is in the stern of the ship.

Stroke- the drummer

and the beat he sets for the oarsmen on a galley.

Top Castle - a

fortified structure on the mast.

Unstep- to take

down the mast.

Weigh Anchor -

means the anchor is clear of the bottom.

[DMG 1e - 55]

The Of Ships and the

Sea (2e) supplement goes into greater detail. So does Ghosts of Saltmarsh for

5e. Stormwrack (3e) goes into even greater detail. These are all good books, but the best early resource is the Martimes Adventures article, “High Seas,” by Margaret Foy, in Dragon

#116. If you have it, great; if you do not, you should get your hands on it.

All other resources pale, by comparison.

I would also suggest using the mariner NPC from DRAGON®

Magazine issue #107 (“For Sail: One New

NPC,” by Scott Bennie). The mariner will not be of much use while in port,

but it’s a potential must-have while at sea.

If you are curious, I’ve added some of the detail from “High Seas” to the end of this piece.

All these resources are terribly useful, but none of them

deals with the prospect of commerce upon the high seas.

Yes, I’m getting that that.

I did find an article in the early issues of Dragon

magazine, by Ronald C. Spencer, Jr, titled, “SEA TRADE IN D&D CAMPAIGNS,” that

was useful. What follows is and excerpt from his article in Dragon #6, April

1977.

The trading system

below gives the player/merchant the opportunity to take risks in hope of

greater reward and also recreates the feeling of insecurity present at seeing

your heavily-laden large merchant sail away, not knowing just how long it will

be gone, or if it will return at all. When a player/merchant decides to

accompany the [vessel] on its voyage the “Wilderness Adventure” rules of

Dungeons & Dragons are used. The rules presented below are intended to

cover a trade business carried on in the absence of the player/merchant under whatever

orders he gives to his ship captain.

SEA TRADE

1. Assumptions — No specific cargo is

required; rather, it is assumed that a cargo can be purchased in any port and

that it will be saleable in any other port. The maximum cargo capacity of a

small merchant is 10,000 G.P. in value; that of a large merchant, 50,000 G.P.

It is not necessary that the maximum be carried if the player/merchant decides

otherwise.

2. Fees and Taxes — There is a pilot fee

for all ports except the merchant’s home port. This fee is 500 G.P. for a small

merchant and 2500 G.P. for a large merchant. All countries have a 5% import

tax, based on the sale value of the cargo-in the receiving port.

3. Profit/Loss — [The] amount of profit or

loss taken on the trip is determined by the number of ports bypassed and a die

roll. The more ports bypassed, the greater the possible profit (or loss!) and

the greater the chance of the vessel being lost due to storms, pirates, sea monsters,

etc.

4. Procedure — The player/merchant “purchases”

a cargo with his on-hand funds and writes a set of sailing orders for the

captain. These should specify what ports to stop at, what profit margin to

accept, how much cargo to buy, and possibly a maximum time to be gone. All this

is delivered to the D/M who will then determine the actual results of the

journey according to the “sailing orders” given him. Note that the

player/merchant will have no knowledge of the results until the ship returns or

word Beaches him of its loss. One important item is that the player/merchant is

not required to sell a cargo at a loss. If he so states in his sailing orders,

a port where a loss would be incurred can be departed and sale attempted at

another port. Note that if this option is chosen, the port departed counts as a

port bypassed. If no specific directions are given to the captain, the cargo

will be sold at whatever profit/loss determined from the Profit/Loss Table.

5. Profit/Loss Determination — Given the

sailing orders, the D/M then rolls the percentile dice, cross-references with

the appropriate “Ports Bypassed” column, and determines the amount of the sale.

Appropriate deductions are made for the pilot fee, taxes, and possibly cost of

a new cargo, and the profit/loss for the port call determined. The D/M then

rolls for the amount of delay there will be before getting underway (due to

repairs, liberty, haggling over prices, etc.) and continue the trip to the next

port as specified by the sailing orders. This procedure continues until the

ship returns to its home port or is lost at sea. If lost at sea, the delay in

reporting it to the player/merchant is rolled for. If the ship returns to its

home port, it is simply a matter of notifying the player/merchant when he and

the ship arrive at the same point in game time.

PROFIT/LOSS TABLE

Percentages

expressed as percent of cargo value

|

%DICE

|

PORTS

BYPASSED

|

|

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6+

|

|

01-05

|

85%

|

80%

|

70%

|

60%

|

50%

|

40%

|

30%

|

|

06-10

|

90%

|

85%

|

80%

|

70%

|

60%

|

50%

|

40%

|

|

11-15

|

95%

|

90%

|

85%

|

80%

|

70%

|

60%

|

50%

|

|

16-20

|

100%

|

95%

|

90%

|

85%

|

80%

|

70%

|

60%

|

|

21-25

|

105%

|

100%

|

95%

|

90%

|

90%

|

85%

|

80%

|

|

26-30

|

105%

|

105%

|

110%

|

115%

|

115%

|

120%

|

120%

|

|

31-35

|

110%

|

110%

|

115%

|

120%

|

125%

|

140%

|

150%

|

|

36-40

|

110%

|

115%

|

120%

|

130%

|

135%

|

160%

|

200%

|

|

41-60

|

110%

|

120%

|

130%

|

140%

|

150%

|

200%

|

300%

|

|

61-75

|

115%

|

125%

|

150%

|

160%

|

200%

|

300%

|

500%

|

|

66-70

|

120%

|

130%

|

160%

|

180%

|

250%

|

400%

|

X

|

|

71-75

|

125%

|

135%

|

180%

|

200%

|

350%

|

X

|

X

|

|

76-80

|

130%

|

140%

|

200%

|

300%

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

81-85

|

140%

|

150%

|

250%

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

86-90

|

150%

|

200%

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

91-00

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X=ship lost, owner notified 3-8 weeks later.

A ship will be

delayed 1-4 weeks at each port (other than its home port). Example of Table: A

ship carrying a 10000 G.P. cargo bypasses one port and the dice are 62. Sale

value is 11500 G.P., less 5% tax and the pilot fee.

[Dragon #6 - 6]

It’s a simple and easy chart. Very useful, I’d say.

It does not cover how ships might be lost; but I think we

all know the answer to that: misfortune, sea monsters, storms. Ships are

becalmed on occasion, and the crew might starve, or succumb to water shortage.

Or disease.

Ships in distress

can suffer a lack of water or food, or a loss of materials for repairs. They

can also be lost or under attack. If a shipwreck is rolled, it can be beached,

shoaled, or shored on a reef or rocks, with or without survivors. (And are they

really survivors or are they dreaded lacedons?) Alternately, the ship could

have already sunk, and the encounter is with survivors in the water, boats, or

rafts. An abandoned ship could be unharmed, a la Marie Celeste. [Dragon #166

– 26 ]

Let’s not forget piracy.

Ship's Capture:

The capturing of a

ship occurs when all the crew aboard one ship have died, surrendered, or are

rendered helpless and unable to fight (trapped in the hold, far example). To

determine if surrender will take place, compare the crews of both sides. If one

side is greater by 3 to 1, surrender is inevitable by the side that is

outnumbered. The captain of the losing side may refuse to surrender and order

his men to continue fighting (a roll of 1 on a d6 indicates that his men will

obey). Surrender does not apply to player characters. They decide whether or

not they want to surrender.

[DMG 1e – 55]

Melee:

Human-like vs. human-like: On-board combat will be as normal melee

combat in a dungeon. Sahuagin, lacedon (ghouls), kopoacinth (gargoyles),

koalinth (hobgoblins) and men (buccaneers and pirates) will attempt to board

the ship. Other human-like creatures such as nixies, aquatic elves, tritons,

sea hags and mermen cannot or will not try to board.

Human-like VS. non-human: The men on a ship will be at a disadvantage

fighting monsters in the water. A squid will try to encircle the ship with its

tentacles and sink it. Other sea monsters may be just as dangerous.

[DMG 1e – 55]

As to those other misfortune, refer to sea encounter

charts, and weather charts found in both the DMG1e and the Wilderness Survival

guide.

All that said, if your PCs wish to travel with their

cargo, all the better; all many of things may happen on the voyage. Roll on the

table, and use that as a starting point for however they wish to negotiate.

From “High Seas”:

On masts and sails:

In order from fore

to aft, the masts on a sailing ship are called the fore, main, and mizzen

masts; on a two-master, they are the main and mizzen masts; and, on a

four-master, they are the fore, main, third, and mizzen masts. A square rig has

square or rectangular sails hanging from the crosspieces on the masts (the

crosspieces are called yards or yardarms). On a fore-and-aft rig, the sails are

shaped like a right triangle. One apex of the triangle is attached to the mast

and another to a traverse beam from the lower mast called a boom. A lateen rig

uses very large sails shaped like a right triangle. The hypotenuse side of a

lateen rigs sail hangs from a very wide yard, and the sail is loose-footed — that is,

without a boom at the bottom. A square rig gives a vessel quite a bit of power,

but requires many sailors to operate. The fore-and-aft rig requires fewer

sailors and is more maneuverable, but delivers less power to the ship. The

lateen rig is midway between the two, both in terms of power and number of

sailors required to handle it. The masts are braced by sets of heavy cables

called the standing rigging, while the ropes used to manipulate the sails,

yards, and booms are called the running rigging. [Dragon #166 – 10]

On Ships:

If the campaign has

an ancient flavor, then use the ancient galleys for warships, pirates, and

privateers, and the cog as a merchant ship. Medieval settings should use the

cog, caravel, carrack, and galleon. Barbarians, especially the ones patterned

after the Vikings, should use the longship. The more advanced types of

commercial small and medium ships are suitable for larger civilized nations

that are noted for their nautical skills.

[Dragon #166 – 26]

Glossary:

Able-bodied

sailor (AB): With one year training. ABs

can make repairs and splice ropes, and know all the knots; in short, they now “know the ropes.” On a galley, they are also the lead rowers, whose actions give the cues to the ordinary sailors. Aft: Rear

half of a vessel, the stern.

Bosun (or

boatswain): In charge of various odd

supplies and the ship’s daily maintenance.

Chief Petty Officer: reports

to the captain; POs report to him.

Decks: Above the orlop deck are the lower, middle,

and upper decks. The crew sling their hammocks on the lower and middle decks,

and on the orlop deck when the ship is very crowded.

Fore: Front half

of a vessel, the bow.

Forecastle: Fore of the foremast, over the upper

deck, where the rest of the petty officers sleep and mess.

Galley: Any vessel

that is rowed and sailed.

Hold: Lowest

space inside the ship, where the cargo and supplies are stored.

Landlubber: No

nautical experience; trainees with less than one-year experience.

Master-at-arms

(PO): Has charge of the ship’s weapons locker, training the crew in combat and administering discipline.

Mates: Assistants

to petty officers. ABs who have special skills.

Midshipmen (middies): Petty

officers in training to become lieutenants.

Ordinary sailor: No special skills, but can go aloft in

the rigging to handle the sails, and on a galley he can be trusted to follow

most commands.

Orlop deck: Above the hold, where there are more

supplies, the hearth, and the crews mess tables; it is also where the wounded

are put during battle.

Petty Officer

(PO): Special skills.

Quarterdeck: Aft of the mizzen mast, over the upper

deck, which roofs over the space where the officers and some petty officers

have their quarters.

Quartermaster (PO): Junior master’s

mate who takes the wheel and steers the ship.

Sailing master

(PO): Navigates the ship and

teaches navigation to the master’s mates and the middies.

Ship: A sailing

vessel, pure and simple.

Small Poop: Over

the quarterdeck. Royal Poop: smaller deck over the small poop.

Waist: Between the

two partial decks, in which the ship’s boats are stored.

The Chain of Command (CoC):

Admiral: commands larger squadrons or fleets, but never a

vessel. Even an admiral’s flagship is commanded by its own captain.

Commodore: the captain of his own ship and commands a

squadron of two to eight vessels.

Captain: Regardless of actual rank, the person commanding

a vessel is called Captain.

Commander: rank above a lieutenant, usually commanding a

caravel, brig, or corvette.

Lieutenants: lowest-ranking commissioned officer is the

lieutenant. Petty officers report to the first lieutenant except for the

sailing master, who reports directly to the captain. Lieutenants frequently

command cogs, cutters, or brigs.

Middies

Sailing Master

Master’s mates

Quartermasters

Bosun

Master-at-arms

If the

master-at-arms dies or is incapacitated, the COC is exhausted and the command

is up for grabs (and so is the vessel, usually). [Dragon #166 – 11]

POs not in CoC:

Carpenter

Cook

Cooper

Cook

Purser

Sailmaker

Marines have their

own officers and command structure. Their highest officer reports to the

captain of the vessel. Their use on vessels is twofold. Firstly, they provide

small missile fire from the decks or fighting tops (the small platforms at the

top of the masts). Secondly, they fight boarding battles. The crew and petty

officers of the vessel load and fire the artillery engines. [Dragon #166 – 11]

Inspirational reading:

Baker, William A. The Lore of Sail. (1983)

Blackburn, Graham. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of

Ships, Boats, Vessels and Other Water-Borne Craft. (1978)

Casson, Lionel. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient

World. (1971)

Cucari, Attilio. Sailing Ships (1976)

Forester, C.S. The Hornblower series.

Melville, Herman. Billy Budd, Omoo, Typee, and (of

course) Moby Dick.

[Dragon #166 – 27]

So, are you inspired to invest in a fleet?

One must always give credit where credit is due. This History is made

possible primarily by the Imaginings of Gary Gygax and his Old Guard, Lenard

Lakofka among them.

Special thanks to Jason Zavoda for his

compiled index, “Greyhawkania,” an invaluable research tool.

The Art:

Ghosts of Saltmarsh Illustration (page 8), 2019

Wilderness Survival Guide Illustration detail (page 46), 1986

The Rime of the Ancient Sea Mariner Illustrations, by Gustave Dore

Crew Illustration, by John Snyder, from Of Ships and Sea (page 35), 1997

Ship and Direction Illustrations, from Dragon #116 (pages 11,12,13,14), 1986

Galley Illustration, from Dragon #6 (page 6), 1977

Shipwreck Illustration, from Dungeon #141 (page 16), 2006

Turtle Dragon Illustration, by Chris Appel, from Stormwrack (page 200), 2005

Sources:

Dragon

Magazine 6,107,166

2011A

Dungeon Masters Guide, 1st Ed., 1979

2020

Wilderness Survival Guide, 1986

2170

Of Ships and the Sea, 1997

Stormwrack, 2005

Ghosts

of Saltmarsh, 2019

SEA TRADE! How have I never seen these rules before? This post could re-spark my Sea Princes game for sure. Way to go David!

ReplyDelete